How the Bauhaus found its way back to Europe

International Modernism: USA

We tend to see the influence of the Bauhaus on the USA as a one-way street. In fact, the fertilisation was reciprocal and continues to this day.

[Translate to English:] headline

The New Bauhaus in Chicago, Walter Gropius’s lectures at Harvard and the many iconic buildings that Mies van der Rohe left behind across the USA: The influence of the Bauhaus in America was mainly spread through its most famous protagonists, all of whom had emigrated there in the second half of the 1930s. And this influence was so widespread that by 1981, American author Tom Wolfe felt compelled to take issue with the nearly canonical architectural dictates of the Bauhaus – flat roofs! no ornament! open floor plans! – and to fight back. In the brilliant short book “From Bauhaus to Our House”, he accused the Bauhausler of, above all, a tabula-rasa mentality, accusing them of historical amnesia and of a blind glorification of novelty as an end in itself.

Of course, Wolfe was wrong. In no way did Bauhaus adherents see themselves as traditionless, as he claimed. After all, the breaking down of boundaries between creative disciplines referred back to medieval workers’ guilds. And the formal principles developed at the Bauhaus in the 1920s did not simply fall from the sky. On the contrary: without the high-rise buildings of the so-called first Chicago School, neither Mies van der Rohe nor Walter Gropius could have developed their early skyscraper designs. There is a slight tendency to view the influence of the Bauhaus on the USA as a one-way street, from Europe to America. Actually, the influence and fertilisation were mutual, and it all began at the end of the 19th century – in Chicago, in fact

[Translate to English:] headline

In 1871 a large part of the city had been destroyed by fire. There was amply sufficient space for new buildings and plenty of money because Chicago was a rich city, but above all there was an imperative, after the catastrophic fire, to build more safely. Architects and engineers began to experiment with new construction methods and, in 1879, for the first time employed a skeleton of structural steel, with which the buildings could literally ascend into the sky. Louis Henry Sullivan was the leader and philosophical guide for this new architectural movement. He not only left behind impressive buildings like the “Auditorium Building” (1886-1889), but also ennobled the new construction method with a social idea. Good architecture is the expression of a democratic social system, he found. Conversely, only persons who “walk the earth in freedom” can be good architects. In 1896 Sullivan also coined the axiom “form follows function”. He insisted the architects of the new towers must find a unique artistic expression for a height that had not previously existed in secular architecture. “Every inch”, he wrote with American self-assurance, must be “a proud and soaring thing.”

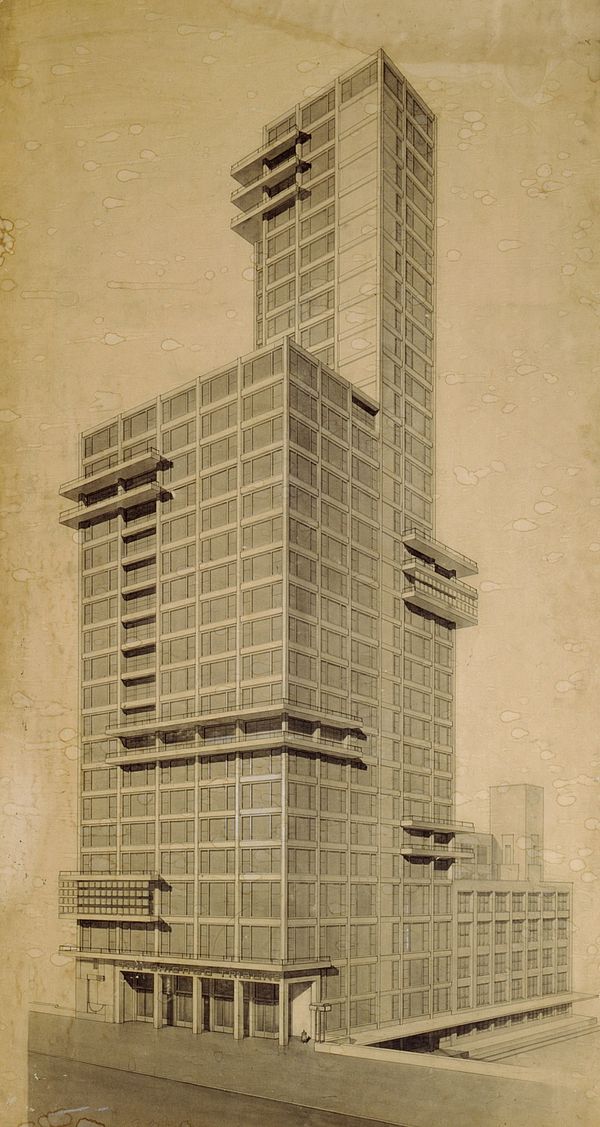

The extent to which the Bauhaus was influenced by this first American architectural modernism is shown not only by the fact that Sullivan’s saying is today mater-of-factly attributed to the Bauhaus. Architects such as Gropius, Mies van der Rohe and others developed their own skyscraper designs, based in part on the Chicago buildings but also in distinction to them. In general, people in Germany were enthusiastic about the towers’ sheer height but found their impact was diminished – if not utterly nullified – by conservative terra-cotta façades or art deco cladding. Mies wrote, “Only skyscrapers under construction reveal the bold constructive thoughts, and then the impression of the high-reaching steel skeletons is overpowering. With the raising of the walls, this impression is completely destroyed ... and frequently smothered by a meaningless and trivial jumble of forms.” Mies himself renounced everything historic in his 1922 competition design for a skyscraper at Bahnhof Friedrichstraße in Berlin. The enclosure, conceived purely of glass, totally avoided any allusions to Gothic style or the mysticism of stained-glass painting. In that same year, Walter Gropius and Adolf Meyer submitted a design to the competition for the Chicago Tribune Tower, which presented European architects with the first opportunity to take on the challenges of an American skyscraper. Although Americans John Mead Howells and Raymond Hood won the competition with a neo-Gothic scheme, Gropius’s design later became the archetype of that which was regarded as a modern tall building. Gropius also worked with a glass façade here, this time modelled on the shapes of the famous Chicago windows and enlivened by a series of balconies. Another aspect, however, is of interest for the internal development of the Bauhaus: at that time, 1922, the conflict was intensifying between Gropius and the mystic Johannes Itten. Like Mies, Gropius no longer interpreted glass as a mirror of infinity, but simply as an industrial building material – thus distancing himself from the expressionist origins of the Bauhaus.

[Translate to English:] headline

The first modernism in America gave birth not only to the tall building but also to the Prairie House style of Sullivan’s famous pupil, Frank Lloyd Wright. But by the end of World War I at the latest, the Chicago School had lost its innovative power. This was in part because architects were by then focusing primarily on the construction of single-family homes. In the mid-1920s, the young art historian Alfred Barr Jr. described contemporary American architecture as a dissatisfying “chaos of architectural styles”.

It was Barr who, almost single-handedly brought the European avant-garde to the USA, and – along with architect Philip Johnson – subsequently became the advocate and patron of the Bauhaus in America. In search of new inspiration, he had travelled through Europe in 1927 and visited the Bauhaus in Dessau, where he met Lyonel Feininger, Oskar Schlemmer, Walter Gropius, Josef Albers and László Moholy-Nagy. He was greatly impressed by the progressive school, so when he was commissioned in 1929 to set up a Museum of Modern Art in New York, he was guided in its creation by the structure of the Bauhaus. The way it broke down the boundaries between disciplines led Barr to exhibit design, photography and architecture alongside paintings.

Barr appointed Philip Johnson, then just 23 years old, to head the architecture department. After Johnson commissioned Mies van der Rohe to design his apartment in 1930, he later claimed to have discovered the architect. In 1932, Johnson and Barr organized the exhibition Modern Architecture: International Exhibition, which was a decisive turning point for the Bauhaus’s rise to prominence in America. Mies van der Rohe and Gropius were each represented by six buildings, one of which was Gropius’s Bauhaus building in Dessau.

But Oskar Schlemmer also played a major role in the Bauhaus legend in the USA – or more precisely, it was his 1932 painting “The Bauhaus Staircase”. Barr and Johnson discovered the work during another trip to Germany at an exhibition in Stuttgart in the spring of 1933 and bought it for the MoMa collection. Schlemmer himself, who regarded the painting as “perhaps ... my best”, was in Breslau at the time and wrote enthusiastically about the interest of the Americans: “I am very pleased that it will go to a worthy, important museum.”

[Translate to English:] headline

“The Bauhaus Staircase” made not only Schlemmer world famous. For decades, the painting hung in a prominent position in the stairwell of the New York museum and came to represent the epitome of the Bauhaus idea, perhaps precisely because it had been made just as the closure of the Bauhaus was imminent: young people stride about within a cool yet seemingly spiritual architecture, advancing toward progress. Or as Schlemmer scholar Karin von Maur wrote: “In the white-red-black chord of the central form, a trio of people’s backs amidst a widely windowed, blue-toned staircase, the theme of ‘humanity as the measure of all things’ – here together with the building of the future – is staged in a really fanfaresque way.”

Incidentally, Alfred Barr travelled once again to Germany in 1936 on a secret mission for Harvard University to negotiate a possible professorship with Mies van der Rohe. It is well known that Walter Gropius, who had maintained good contacts in the USA since his first trip to America in the late 1920s, was then appointed to Harvard, while Mies was offered the position to head the architecture department at the Armour Institute in Chicago in 1938. Prior to that, László Moholy-Nagy had also already moved to Chicago, where, as arranged by Gropius, he took over direction of the planned New Bauhaus – American School of Design. This marked the beginning of the triumphal march of Bauhaus aesthetics into architecture and design, albeit limited solely to purely formal aesthetic values. The socio-political concepts on which they were once based hardly played a role. The Bauhaus in America was, for all practical purposes, merely a matter of style.

Less well known is that the performing arts as taught at the Bauhaus also exerted a strong fascination on American artists – and their works found their way back to Europe. Shortly after the Nazis seized power in 1933, Josef and Anni Albers emigrated to the USA and assumed direction of the Black Mountain College in North Carolina. Here, in rural seclusion, young students were offered courses in art, literature, music and theatre. Xanti Schawinsky, a former member of the Bauhaus theatre, joined them in 1936 – and with him, experimental theatre and dance arrived in America. The roots of what is now called performance art developed there in an intense and at the same time intimate family atmosphere. John Cage also taught at Black Mountain College and, together with Robert Rauschenberg, performed the piece Untitled Event in 1952.

In 1957, another cycle of cross-fertilisation came full circle: four Düsseldorf artists founded the group ZERO, whose light, air and wind chimes explicitly made reference to the kinetic objects and experiments of László Moholy-Nagy. Zero stands for the “immeasurable zone in which a former state transitions into an unknown new one”, as co-founder Otto Piene described it. This in turn made the group itself an inspiration for American artists such as Dan Flavin or James Turrell – who continues to experiment with light and natural phenomena today.

- Barry Bergdoll: Hüllen aus reinem Glas für einen neuen Architektonischen Ausdruck. In „Modell Bauhaus“, Hatje Cantz, 2009.

- Bart Lootsma: Der Wettbewerbsentwurf für den Chicago Tribune Tower von Walter Gropius und Adolf Meyer. In „Modell Bauhaus“, Hatje Cantz, 2009

- Margit Kentgens-Craig: Bauhaus-Architektur – Die Rezeption in Amerika 1919 – 1936. Peter Lang Verlag, 1993.

[AS 2018, Translation DK]