The New Man on the Move

Bauhaus as a Festival

While the Bauhaus parties in Weimar are still largely exclusive, the celebrations in the new Bauhaus building in Dessau have been opened to a broader public, with the result that they now serve as public relations events for the school. Attendees can expect to experience the ways in which the Bauhaus educated its students to develop self-confident, bold, adventurous personalities in terms of design.

[Translate to English:] Absatz 1

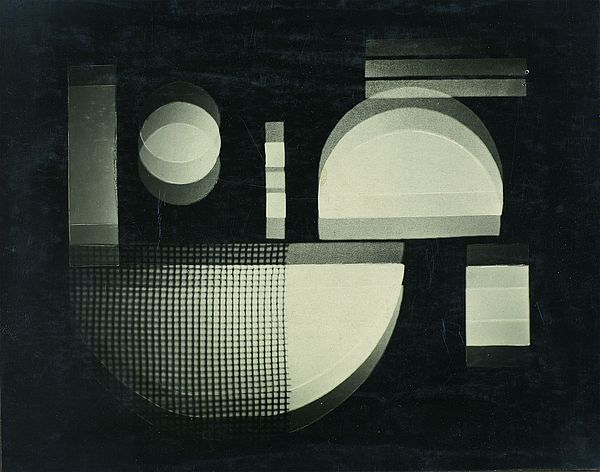

Most notable among these events was the “Metallic Party” or the “Glocken-Schellen-Klingel-Fest” [Church Bells, Doorbells and Other Bells Party], a carnival celebration which took place on February 9, 1929 at the Bauhaus in Dessau and went down in art history. One reason for its enduring fame is that there are more surviving pictures from the Metallic Party than from any other Bauhaus party. One well-known photo is of Marianne Brandt and shows her wearing extraordinary jewelry: a chrome-plated brass dish on her head and a thick collar around her neck. Most of the legendary images from this party are snapshots, but some are orchestrated photos which have become well-known through countless illustrated books about the Bauhaus. The composed photographs, more than anything else, shatter the perspective of a mere likeness through the use of mirror images, multiple exposures and fragmentation which shape our contemporary ideas concerning the dynamism of Bauhaus life.

[Translate to English:] Absatz 2

People at the Bauhaus were fascinated by the then still new media of cinema and the telephone. They witnessed the beginnings of television, the new style of neon signs in the big cities, the technical culture of amusement parks, variety shows and revues, magazines and, in general, a newly developing culture of urban leisure and consumerism. A promising new mass society was emerging which, based on industrial serial manufacturing and the mass production of goods and housing, could bring about a new prosperity that transcended the boundaries of class and social strata. Without ignoring the clearly visible social and economic tensions, the capitalist reality, people nevertheless believed that there were enough reasons to be positive and affirmative toward the latest technical developments.

They interpret, accentuate, distort, and orchestrate, often with a magical effect. At the Metallic Party, the dominance of reflective metal, in and of itself, offered a special opportunity to produce these types of photograph. It seems as if these images were intended to give expression to the inspiring power of the Bauhaus concept, the “Utopia of the New Man,” through a new way of seeing.

[Translate to English:] Absatz 3

Accordingly, they experimented with electrical cinematic devices in stage workshops. Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack built an apparatus for generating “moving reflections of colored light.” László Moholy-Nagy developed a “light-space modulator,” which was actually a “light prop for the electric stage” between 1922 and 1930. The “Total Theater,” was designed in 1927 by Walter Gropius for Erwin Piscator’s Volksbühne [People’s Theater] in Berlin as a new kind of theatrical apparatus, whereby the stage space was constantly being transformed, and gigantic projection devices were able to create an atmosphere in which the audience and performers could experience themselves as common members of a new mass collective. Despite all the differences between their approaches to artistic and creative issues, the Bauhaus members incorporated a thoroughly positivist attitude; the will to always make the best of prevailing conditions and take on the challenge of the mechanization and industrialization of the working and living environments. The Bauhaus parties perhaps reflected this common attitude, as more than a few objects, such as Wilhelm Wagenfeld’s Bauhaus lamp, Marcel Breuer’s tubular steel furniture or the cubic Bauhaus architecture by Walter Gropius, have now become design icons. Seen in this light, the Bauhaus parties can also be described as works of art in which the entire Bauhaus collective—or the Bauhaus as an artistic working and living community—has been staged and presented more comprehensively than anywhere else. Gropius’ vision of a new spatial art which he described in his 1923 article “Concept and Structure of the Bauhaus” was ultimately manifested in the parties as a great overall vision: “All artistic work aspires to design space. But if each subwork is to be related to a larger whole, and this must be the goal of the new drive to build, then the actual and intellectual means of spatial design must be masterful and known by all who are united in the joint endeavor. And this is where there is a great confusion of terms. What is space, and how can we capture and shape it? and so forth. A vibrant, living artistic space can only be created by those whose knowledge and ability obeys all the natural laws of statics, mechanics, optics, and acoustics and who find in their common mastery the sure means, the cerebral concept that it carries within itself, to bring it to life. In the artistic space, all the laws of the real, cerebral and spiritual world find a simultaneous solution.”

About the Author

Torsten Blume (Dessau) works as a research associate, artist and choreographer at the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation.

[Translate to English:] Absatz 4

Looking back, Felix Klee, the son of Paul Klee, reported, “There was a small party at the Bauhaus every weekend. And every month, they threw a large costume party with some amusing theme. Four parties, one for each season, were the highlights.” At these parties, which were, for the most part, initiated and coordinated by the members of the stage workshop, the Bauhaus was celebrated as an avant-garde, future-oriented artist’s community. On the other hand, installations and individual performances as well as marketing always took place in transitionally-staged spaces. Its purpose: the overall goal of the Bauhaus is to demonstrate the design of a new modern living environment to the increasing number of guests appearing from around the world while bearing audience appeal in mind.