The Art of Memory

Robert Wilson plays “Krapp’s Last Tape”

By Rüdiger Schaper

The World as Vaudeville and Representation: Samuel Beckett’s heroes frequently awaken the impression that they are failed, errant actors, remembering their earlier roles and playing through them once again. Therefore they are also always stuck in a specific situation, designated by the author, carrying an invisible housing around with them. Beckett texts set stage spaces on the stage. So not only are the players doubled – actors play actors, who are actors, space and time also stand side by side. Director, designer and performer Robert Wilson, not much of a psychology and realism fan, finds himself confronted with this. In an interview he says: “Naturalistic theatre always looks artificial for me. I need make-up, masks, costumes – illusion! I need light on the stage, lots of light.”

In his Hamlet solo, Robert Wilson not only played all the roles of Shakespeare’s drama, he also embodied and evoked all their voices on the stage – the mother’s, the uncle’s, Polonius’s and Ophelia’s. In the prince’s monologues he also handled the pitches, the diction of famous historical Hamlet actors such as Joseph Kainz and Alexander Moissi. He took their voices, their German recital from Schellack records and transported them to his English-language delivery. Wilson’s higher and more hysterical Texan chant is wonderfully enhanced by the declamation style of the forgotten theatre heroes of the late 19th and early 20th century. Asta Nielsen’s silent film Hamlet has slipped nicely into Wilson’s one-man show as well.

The Art of Memory part 2

His connection with Europe and the European avant-gardes is evident. His theatre resembles a buzzing, shimmering museum. Along with the ballet art of one George Balanchine and Japanese presentation aesthetics, the expressionism and German silent film stand out here, and once again he draws it into the grotesque. In his stage architecture we sense influences of the theatre visionary Edward Gordon Craig and the Bauhaus – Wilson’s relationship with Oskar Schlemmer is rarely noted. It is expressed very clearly in the mannequin-like features of his figures and the proximity to dance. Schlemmer’s Triadic Ballet, the geometrical feeling and the colour philosophy of the performing Bauhaus artist – it’s all part of the pool from which Wilson has built his beautiful old and always as if new and flashing world. His stage objects, which we really can’t call props, also follow a clear formal aesthetic and function. Robert Wilson is also a passionate collector of every conceivable kind of artefact. He loves chairs in particular.

The Texan’s career ran via Paris, where of course Samuel Beckett also lived. International fame came in 1971 with the production in the French capital of his four-hour opera “Deafman Glance”. Louis Aragon was so inspired that he spoke in an open letter of a, “miracle that we had been waiting for.” In 1976 and again in France followed the opera “Einstein on the Beach” with the mantra-esque music of Philip Glass. He has since been rooted and regarded more in Europe in artistic terms than in the USA. The Louvre opened itself for Robert Wilson and his electronic “Lady Gaga Portraits”, in which the pop artist posed in the pictorial worlds of Ingres and Jacques-Louis David.

Wilson loves the stars of the past. And of course nothing vanishes in his theatre cosmos. He likes to quote Marlene Dietrich: “You have to place the voice with the face” – so the singer’s or actor’s face gives space to the voice, so to speak. The face makes the voice visible. And the voice has a visible effect at the eyes and the mouth. With Wilson the notes come from a certain coldness. He stages cold light, and his actors’ movements are secretly described as slow, which, however, is only half the story. Because, what is fast? What does cold mean? What does abstract mean in this context? Wilson is elementary in observing all.

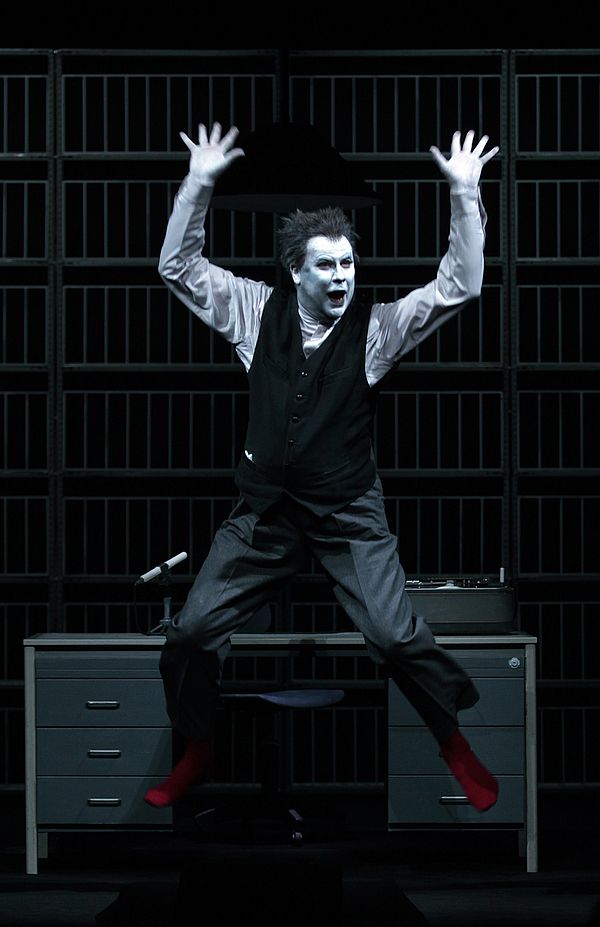

“Krapp’s Last Tape” by Samuel Beckett, world première in 1958 in London, is a festival for an older actor. Martin Held, Bernhard Minetti, Klaus Maria Brandauer, Josef Bierbichler have interpreted Krapp in the German-language theatre world. A broken creature was often seen here, bent over the audiotape, plagued by the ghosts of the past, an “Endgame” without partners. Wilson is more powerful in tackling the theatrical piece. His jarring appearance transcends all sorrow. And nor is there any sympathy for a lonely old man. This Krapp is not especially sympathetic, small children would be frightened by his sharp cries and malicious poses. A white made up magician-clown is presented here as circus trainer of collective memories. As in Hamlet, he takes voices “out walking”, listens to his inner self, the world is a cosmos of sharply structured light conditions and sound sequences. Krapp’s stage could be a studio, an electronic archive, a control room. Wilson the actor mixes a comic figure with King Lear. The hair stands on end, a reminiscence of and tribute to Albert Einstein. The 20th century is paraded past – with animal-comic sounds of Mr Walt Disney, with the grimaces of French mime and memoirs of music hall days, from the depth of the room, putting us in mind of a nuclear bunker. A cyborg could have taken possession of the Krapp role and eavesdropped on the human vocalization on the old tapes. As mechanically as Wilson’s Krapp slings his Beckett’ian bananas, it appears entirely possible that an artificial intelligence learns a text here, which an actor has left behind for posterity, but which they had given very little chance of survival. Krapp’s Last Tape is full of his early love. A scene from a piece played out, damned to eternal repetition.